Wednesday, December 5, 2012

Copyright, It's The Law!

“If business is not for you, then the art world is not for you.” Tracey Emin.

The statement made by Emin in her famous heated interview with John Humphry’s back in 2004 on the BBC Radio 4’s “Today” programme, controversial yet she speaks the truth. The artist is a self employed entrepreneur. Much to my amazement, there is much to learn as a self employed artist, effectively running your own business and all the legalities this brings. After all my years training in art college, I’ve had to embark on finding all legal, financial, regulatory information and copyright laws out on my own. The opportunity to prepare art students for the real world is overlooked and instead year after year art students continue to be churned out from educational institutes with little or no knowledge of these essential practices for artists and designers. So much for a rounded education!

The legality behind copyright has always intrigued me so this will be the area of discussion. The fact that copyright is automatic from the moment of artistic creation, lasts for life AND a further 70 years after death. Yet its worth noting that if you are an employee, the employer will own all copyright to creative output. Its vital that if you are self employed, you must retain ownership and avoid selling rights of art works.

Un registered design rights, offer limited protection for designers, these rights last for 15 years after the object has been made and 10 years after the first marketing of the product. Its important to note that after 5 years from the moment of manufacture or marketing, others have the right to manufacture your products, after they have obtained your permission.

When a designer is commissioned to create a design, the commissioner automatically has “unregistered rights” to your design. Its up to the designer to negotiate ownership of rights, as under implied law clients have legal right in commission agreements. While the use of trademark ™ protects names, brands and logos etc, its used when a business hasn’t officially registered with the Intellectual Property Office (IPO.) Registering a trademark can be a complicated affair but IP law covers things from business names, brands, illustration, smells and even artists or designers name. When selling an art work its vital to negotiate a licensing agreement with the purchaser. This contract must be written and should include information regarding the duration of the licence, the permitted uses of the design, ie bags, t-shirts, billboards etc. Also indicate the country or region where the licence applies. The licence agreement is separate to overall copy right, licensing allows the client limited rights to the artwork / design they purchased, for the limited time, location, use, listed in the agreement contract. The overall copyrights always lie with the artist, unless the rights have been sold on.

For further information regarding copyright laws in Ireland consult, www.icla.ie

Thursday, November 8, 2012

Monday, September 17, 2012

The Compulsion To Create : 12 Striking Tendencies of Creative People

Ever wonder what makes those wacky, creative types tick? How is it that some people seem to come up with all kinds of interesting, original work while the rest of us trudge along in our daily routines?

Creative people are different because they operate a little differently. They:

Do you consider yourself creative? (Say yes.) Finding something you’re really passionate about will help you take a chance and might just result in something wildly creative.

Courtesy of 12most.com

Creative people are different because they operate a little differently. They:

1. Are easily bored

A short attention span isn’t always a good thing, but it can indicate that the creative person has grasped one concept and is ready to go on to the next one.2. Are willing to take risks

Fearlessness is absolutely necessary for creating original work, because of the possibility of rejection. Anything new requires a bit of change, and most of us don’t care for change that much.3. Don’t like rules

Rules, to the creative person, are indeed made to be broken. They are created for us by other people, generally to control a process; the creative person needs freedom in order to work.4. Ask “what if…”

Seeing new possibilities is a little risky, because it means that something will change and some sort of action will have to be taken. Curiosity is probably the single most important trait of creative people.5. Make lots of mistakes

A photographer doesn’t just take one shot, and a composer doesn’t just write down a fully realized symphony. Creation is a long process, involving lots of boo-boos along the way. A lot goes in the trash.6. Collaborate

The hermit artist, alone in his garret, is a romantic notion but not always an accurate one. Comedians, musicians, painters, chefs all get a little better by sharing with others in their fields.7. Are generous

Truly creative people aren’t afraid to give away their hard-earned knowledge. The chef can give you the recipe because she knows you won’t make it like she does anyway.8. Are independent

Stepping off the beaten path may be scary, but creative people do it. Children actually do this very well but are eventually trained to follow the crowd.9. Experiment

Combining things that don’t normally go together can result in brilliance or a giant mess. Trial and error are necessary to the creative process.10. Motivate themselves

There does seem to be a spark that creative people share, an urgent need to make things. They are willing to run the inherent risks of doing something new in order to get a new result.11. Work hard

This is probably the most overlooked trait of creative people. People who don’t consider themselves to be creative assume that people who are creative are magical, that ideas just pop into their heads effortlessly. Experienced creative people have developed processes and discipline that make it look easy.12. Aren’t alone

The good news is that it’s possible for everyone to be creative. There are creative accountants, creative cooks, creative janitors, creative babysitters. Any profession or any hobby can be made into a creative pursuit by embracing and using creative traits.Do you consider yourself creative? (Say yes.) Finding something you’re really passionate about will help you take a chance and might just result in something wildly creative.

Courtesy of 12most.com

Friday, August 31, 2012

Forgotten

The "Forgotten" series is a response to socities view of the elderly.

All images are screen printed or etches.

Check out more of my work on my online portfolio:

Saturday, August 18, 2012

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

Artists On The Dole In Ireland

An interesting article which i came across during the week in the Irish Times, regarding the role which the dole plays for struggling artists, although highly educated does their education get them anywhere?!. A depressing read for any art graduate but i feel this information should be available for students who are thinking about a career in the arts.

Role of the dole: How benefits benefit artists

The Irish Times

Sat 4th Aug

Without ‘the other arts council’, almost a quarter of artists would earn nothing while – and sometimes after – spending years on a body of work. The artist is alive and well in the garret, writes PATRICK FREYNE

IT HAS LONG been seen as “the other arts council”. Generations of musicians, artists, film-makers, actors and writers – including this journalist, in a former life as a musician – have spent time working on their art unpaid and with the help of the Department of Social Protection. Those in the culture industries generally recognise this as a necessary fact of life. In order for Ireland to develop a clutch of James Joyces, Riverdances and U2s to cement its arts reputation internationally, thousands of committed artists must toil for little or no reward.

Before the welfare state, the options for artists were: have rich relatives, find a wealthy patron or starve in a garret. After the welfare state those who might never have had the option to create could do so while on the dole. There are high-profile examples. JK Rowling wrote the first instalment of the Harry Potter sequence while living on benefits. Many of the punk, post-punk and pop bands of the 1970s and 1980s were formed in the dole queue.

“Without the [dole] you wouldn’t have had The Specials. You wouldn’t have had UB40. You wouldn’t have had The Clash,” says Peter Murphy, the writer of acclaimed novel John the Revelator and, a long time ago, a musician on the dole. “Now, it’s worth arguing that these kinds of bands were so ambitious and resourceful they might have figured it out one way or another . . . But the reality is that if you dedicate your life to the arts you’re essentially taking a vow of, if not poverty, then extremely menial living.

“If you work for four years on a book and someone gives you 50 grand it sounds like a lot of money, but if you break that up over four years of writing, and four years of learning how to write in the first place, that’s a very menial wage. Some newspapers like to portray artists as hookah-smoking Oscar Wilde dandy types sitting by a turf fire, but the reality is, I’m afraid, far more North of England kitchen-sink drama.”

In The Living and Working Conditions of Artists, a report published by the Arts Council in 2010, 23 per cent of the artists surveyed had registered as unemployed in the previous year. In 2008, according to the report, artists earned less than €15,000 from their art. Noel Kelly, the director of Visual Artists Ireland, says 37.5 per cent of the visual artists it surveyed last year had received assistance during the past five years. “Most depend on other sources of income, on the income of spouses or on the dole.”

The current economic conditions mean artists are particularly dependent on that very meagre latter option. “We have graduates getting out of college now who would traditionally have subsidised an art career [with a job] in academia, but all those jobs have gone,” says Kelly. He stresses that these people work very hard and do not want to receive the dole. “Artists are constantly asked to do stuff for nothing. Some exhibitions are great and pay artists a small stipend, but there are many organisations that just don’t have any money and artists are so willing to show their work that they work for them anyway. Artists often work for two or three years on a body of work with no money until the end.”

Frank Buckley, the artist behind the Billion Euro House in Smithfield, in Dublin’s north city, a construction made of decommissioned bank notes, is on the dole. “Over the past eight months my work has been seen in 113 countries and featured in national newspapers all over the world. People just presume you’re making money when they see that. When you tell them about the reality, they say, ‘Ah sure, it’s only a matter of time . . . you’re famous.’ But I live on €188 a week. My mortgage is in arrears, and only for the guy giving me [an empty office building on Coke Lane] to use, I wouldn’t be able to do this.”

This perception of success can lead to problems when artists turn up at the dole office, and Kelly says the way the system deals with artists is inconsistent. “Of those we surveyed who had sought social welfare, 23 per cent were told to apply for alternative jobs, 14 per cent were threatened with the removal of benefits and 27 per cent noted variations between social-welfare officers. A lot of them are encouraged to get out of the arts.”

This is a shame, because art needs time. Jinx Lennon, Dundalk’s fine political songwriter and punk poet, who is playing at the Liss Ard festival today, says his own artistic development benefited greatly from an involuntary spell of unemployment a decade ago. “At the moment I have a sort of a night job,” he says. “About 10 or 11 years ago I wasn’t working. I didn’t have much money but I found something that was worth a lot more – the ability to create. I was on the dole and I could have used that time vegetating or getting stoned or watching TV, but I decided I had a lot to write about and I needed to get it out. It was about finding my art, if you like. The anger or the energy I had from being on the dole: I found that if I could just get the thoughts down on paper that was really, really good. And now I’m really grateful for that time because I was able to start and give myself a kick.”

Julian Gough, a novelist, musician and playwright (see Culture Shock, below), who also left the dole queue a long time ago, agrees that when it comes to art, time is of the essence. “Samuel Beckett had a very modest private income, James Joyce had hand-outs from Sylvia Beach and my generation had the dole,” he says. “It’s how most artists I know bought the time to become good at what they do. Without it I don’t think we’d have had any of the great artists, stand-ups, writers or actors we’ve seen in recent decades . . . You have to immerse yourself completely in your art to become good at it and the dole is one of the only ways a lot of people can achieve that.”

Obviously, this subject raises questions about the role of welfare. Many feel that unless artists make their art work economically in the short term, they should change profession. However, most successful artists did not start their careers with economic success, or even solvency, and nobody wants art to be the province of the independently wealthy. “It would be really interesting if there was someone in every social-welfare office who was at least trained in or had some facility with the arts and could engage with artists coming in to claim the dole,” says Murphy. “It would be very forward thinking and progressive if artists could come in and sit down and honestly say, ‘Here’s what I’m doing. Here’s my work and here’s what the Arts Council says. I’m not taking the mick.’”

Kelly has been trying to arrange a meeting between Visual Artists Ireland and the Minister for Social Protection to discuss the problems struggling artists have with the system. He is also advocating a version of the New Deal of the Mind that operates in the UK. The scheme references the original New Deal in the US in the 1930s, which included unprecedented levels of state funding to the arts during the Great Depression. “The New Deal of the Mind takes the deficit of staff in the culture sector and matches it with artists registered as unemployed and looking for additional employment,” says Kelly. “There are all these cultural institutions around the country that can’t deliver the programmes they have because they don’t have the staff. This could address that and give artists work.”

Gough thinks it’s important to make explicit something that’s usually just a whisper: that the actors, writers, artists and film-makers who enrich our culture often need to claim benefits. “The dole is incredibly significant for the arts in Ireland, and that’s not well acknowledged,” he says. “It’s not a luxurious life, by any means. It might be nice if artists could get a modest income to acknowledge that what they’re doing is culturally useful. It would have to be less than the dole, though, to stop people pretending to be artists to get it.” He laughs. “Maybe just a symbolic euro less.”

Role of the dole: How benefits benefit artists

The Irish Times

Sat 4th Aug

Without ‘the other arts council’, almost a quarter of artists would earn nothing while – and sometimes after – spending years on a body of work. The artist is alive and well in the garret, writes PATRICK FREYNE

IT HAS LONG been seen as “the other arts council”. Generations of musicians, artists, film-makers, actors and writers – including this journalist, in a former life as a musician – have spent time working on their art unpaid and with the help of the Department of Social Protection. Those in the culture industries generally recognise this as a necessary fact of life. In order for Ireland to develop a clutch of James Joyces, Riverdances and U2s to cement its arts reputation internationally, thousands of committed artists must toil for little or no reward.

Before the welfare state, the options for artists were: have rich relatives, find a wealthy patron or starve in a garret. After the welfare state those who might never have had the option to create could do so while on the dole. There are high-profile examples. JK Rowling wrote the first instalment of the Harry Potter sequence while living on benefits. Many of the punk, post-punk and pop bands of the 1970s and 1980s were formed in the dole queue.

“Without the [dole] you wouldn’t have had The Specials. You wouldn’t have had UB40. You wouldn’t have had The Clash,” says Peter Murphy, the writer of acclaimed novel John the Revelator and, a long time ago, a musician on the dole. “Now, it’s worth arguing that these kinds of bands were so ambitious and resourceful they might have figured it out one way or another . . . But the reality is that if you dedicate your life to the arts you’re essentially taking a vow of, if not poverty, then extremely menial living.

“If you work for four years on a book and someone gives you 50 grand it sounds like a lot of money, but if you break that up over four years of writing, and four years of learning how to write in the first place, that’s a very menial wage. Some newspapers like to portray artists as hookah-smoking Oscar Wilde dandy types sitting by a turf fire, but the reality is, I’m afraid, far more North of England kitchen-sink drama.”

In The Living and Working Conditions of Artists, a report published by the Arts Council in 2010, 23 per cent of the artists surveyed had registered as unemployed in the previous year. In 2008, according to the report, artists earned less than €15,000 from their art. Noel Kelly, the director of Visual Artists Ireland, says 37.5 per cent of the visual artists it surveyed last year had received assistance during the past five years. “Most depend on other sources of income, on the income of spouses or on the dole.”

The current economic conditions mean artists are particularly dependent on that very meagre latter option. “We have graduates getting out of college now who would traditionally have subsidised an art career [with a job] in academia, but all those jobs have gone,” says Kelly. He stresses that these people work very hard and do not want to receive the dole. “Artists are constantly asked to do stuff for nothing. Some exhibitions are great and pay artists a small stipend, but there are many organisations that just don’t have any money and artists are so willing to show their work that they work for them anyway. Artists often work for two or three years on a body of work with no money until the end.”

Frank Buckley, the artist behind the Billion Euro House in Smithfield, in Dublin’s north city, a construction made of decommissioned bank notes, is on the dole. “Over the past eight months my work has been seen in 113 countries and featured in national newspapers all over the world. People just presume you’re making money when they see that. When you tell them about the reality, they say, ‘Ah sure, it’s only a matter of time . . . you’re famous.’ But I live on €188 a week. My mortgage is in arrears, and only for the guy giving me [an empty office building on Coke Lane] to use, I wouldn’t be able to do this.”

This perception of success can lead to problems when artists turn up at the dole office, and Kelly says the way the system deals with artists is inconsistent. “Of those we surveyed who had sought social welfare, 23 per cent were told to apply for alternative jobs, 14 per cent were threatened with the removal of benefits and 27 per cent noted variations between social-welfare officers. A lot of them are encouraged to get out of the arts.”

This is a shame, because art needs time. Jinx Lennon, Dundalk’s fine political songwriter and punk poet, who is playing at the Liss Ard festival today, says his own artistic development benefited greatly from an involuntary spell of unemployment a decade ago. “At the moment I have a sort of a night job,” he says. “About 10 or 11 years ago I wasn’t working. I didn’t have much money but I found something that was worth a lot more – the ability to create. I was on the dole and I could have used that time vegetating or getting stoned or watching TV, but I decided I had a lot to write about and I needed to get it out. It was about finding my art, if you like. The anger or the energy I had from being on the dole: I found that if I could just get the thoughts down on paper that was really, really good. And now I’m really grateful for that time because I was able to start and give myself a kick.”

Julian Gough, a novelist, musician and playwright (see Culture Shock, below), who also left the dole queue a long time ago, agrees that when it comes to art, time is of the essence. “Samuel Beckett had a very modest private income, James Joyce had hand-outs from Sylvia Beach and my generation had the dole,” he says. “It’s how most artists I know bought the time to become good at what they do. Without it I don’t think we’d have had any of the great artists, stand-ups, writers or actors we’ve seen in recent decades . . . You have to immerse yourself completely in your art to become good at it and the dole is one of the only ways a lot of people can achieve that.”

Obviously, this subject raises questions about the role of welfare. Many feel that unless artists make their art work economically in the short term, they should change profession. However, most successful artists did not start their careers with economic success, or even solvency, and nobody wants art to be the province of the independently wealthy. “It would be really interesting if there was someone in every social-welfare office who was at least trained in or had some facility with the arts and could engage with artists coming in to claim the dole,” says Murphy. “It would be very forward thinking and progressive if artists could come in and sit down and honestly say, ‘Here’s what I’m doing. Here’s my work and here’s what the Arts Council says. I’m not taking the mick.’”

Kelly has been trying to arrange a meeting between Visual Artists Ireland and the Minister for Social Protection to discuss the problems struggling artists have with the system. He is also advocating a version of the New Deal of the Mind that operates in the UK. The scheme references the original New Deal in the US in the 1930s, which included unprecedented levels of state funding to the arts during the Great Depression. “The New Deal of the Mind takes the deficit of staff in the culture sector and matches it with artists registered as unemployed and looking for additional employment,” says Kelly. “There are all these cultural institutions around the country that can’t deliver the programmes they have because they don’t have the staff. This could address that and give artists work.”

Gough thinks it’s important to make explicit something that’s usually just a whisper: that the actors, writers, artists and film-makers who enrich our culture often need to claim benefits. “The dole is incredibly significant for the arts in Ireland, and that’s not well acknowledged,” he says. “It’s not a luxurious life, by any means. It might be nice if artists could get a modest income to acknowledge that what they’re doing is culturally useful. It would have to be less than the dole, though, to stop people pretending to be artists to get it.” He laughs. “Maybe just a symbolic euro less.”

Friday, June 22, 2012

Four-year-old artist Aelita Andre exhibits in NY

Artist Aelita Andre might only be four years old, but that has not stopped her opening her first art exhibition in New York.She is said to be the youngest ever professional artist with nine of her paintings on show at the Agora Gallery, in Manhattan, already selling, with pieces priced up to $9,900 (£6,000) each.

Angela Di Bello, the director at the gallery, said Aelita had already developed a style of her own.

Her parents, Nikka Kalashnikova and Michael Andre, who are also artists, both agree that their daughter's art has an innocence to it.

Saturday, June 9, 2012

10 Things Every Graduate Should Know Before They Start Job Hunting

Yet another great article courtesy of The Guardian:

Despite lower salaries, more unpaid positions and a recession, it's not all doom and gloom for graduate jobseekers

Illustration: Guardian

Tanya de Grunwald

The Guardian, Fri 1 Jun 2012

If the 370,000 students set to graduate from UK universities this summer know just one thing, it's that the party is over. Figures from employment website Totaljobs show one in three graduates is claiming jobseeker's allowance and a quarter of graduates haven't had a single interview.

Huge numbers of roles posted on graduate "job boards" are, in fact, lengthy unpaid internships – and research from Incomes Data Services found that those lucky enough to find paid work will discover their starting salary is 2% lower than it was for the class of 2011.

Certainly, 2012 is a tough year to graduate – but there is still a great deal that jobseekers can do to boost their chances of finding employment. Frustratingly, it seems little of this advice is reaching them – of the hundreds of recent graduates I met while writing How to Get a Graduate Job in a Recession, few felt confident about tackling the task ahead.

Many say they found their university careers service uninspiring and unhelpful – that's if they made it through the door. So what are the things the class of 2012 really needs to know?

1 Unpaid internships are illegal

The biggest issue for today's graduates isn't joblessness – it is unpaid internships. According to Interns Anonymous, a quarter of interns have done three or more placements, and one in four internships lasts more than six months. Increasingly, it's a myth that unpaid internships lead to paid jobs; now they are replacing paid jobs.

There is no legal definition of an intern, but national minimum wage law states anybody who qualifies as a worker must be paid at least £6.08 an hour (if aged 21 and over) unless their employer is a charity. If an intern's role has set hours and responsibilities and the person is contributing work that's of value to their employer, it's likely the company is breaking the law. Yes, even if the intern says they're happy to work for nothing.

The problem is that the law simply isn't being enforced – and making this happen is proving difficult. Happily, the UK has the most active interns' rights movement in the world (this is a global problem).

Graduate Fog (which I founded) and Intern Aware has just launched Interns Fight for Justice, a campaign aimed to help interns take their high-profile former employers to a tribunal.

2 Ignore the headlines – there are still jobs out there

News that 83 graduates apply for every job is eye-catching, but is it really true? The big graduate schemes may be over-subscribed, but a major PR agency received just six applications for a junior account executive job paying £24,000. Are graduates only applying to the big names, via adverts they've seen in the most obvious places?

"Doom and gloom makes headlines but, believe it nor, not there is a huge shortage of bright, employable graduates," says James Uffindell, founder of recruitment site Bright Network. "The war for talent is back on. Major blue chip recruiters and fast-growing startups are recruiting again. We're helping consulting firms, media businesses, hedge funds and many other enterprises find the talent they need to grow their businesses."

3 Doing more education isn't the answer

A second degree means a better job – or at least a better chance of getting a job. Right? Wrong. Think carefully before you sign up for an expensive postgraduate course that may be of little interest to employers – and beware of the increasingly slick marketing methods used by universities (remember, education is a business now).

"Many graduate recruiters are happy with an undergraduate degree – few job adverts stipulate a postgraduate qualification," says Dan Hawes, head of marketing at Graduate Recruitment Bureau.

Candidates with a postgraduate degree shouldn't expect a higher salary either. "After degree level, earnings actually decrease the more educated someone is," adds Uffindell.

Don't view postgraduate study as a genius ploy to "wait out" the recession. Who says things will be better in 12 months? In 2013 you'll be competing with a new batch of graduates – plus those who didn't find work this year.

4 Give the industry you have chosen a health check

The digital revolution has turned many industries upside down. The music industry, book publishing and print journalism are obvious examples, but other industries are suffering, too. This means the "dream jobs" you've set your heart on may not even exist in a few years – and if they do, they could be poorly paid and insecure.

Graduates often hope that if they want their goal badly enough, they'll get there. Sadly, this isn't true. Look around. If people established in your chosen industry are bailing out, what does that tell you? Think laterally and take your skills to a growing sector. Your career spans 40 years. Don't pick an industry that will be dead in five.

5 The perfect CV is a myth

Graduates obsess about crafting the perfect CV, but there's no such thing. If yours is clear and concise, stop fiddling. And forget about trying to stand out. If your application is really good, it will get noticed.

Instead, use the extra time to check your online footprint. "Google yourself. What comes up – and how does it make you look?" says James Whatley, social media consultant at Social@Ogilvy. "Potential employers will do this – so make sure you've done it first." Use Facebook's new "view as" button (found under the "edit profile" settings) to see how your non-friends can see you – and adjust the privacy settings accordingly. "Next, set up your LinkedIn profile. It's a brilliant place for hearing about jobs on the grapevine. Keep adding new training and skills you pick up, so it's always bang up to date," adds Whatley.

6 Don't forget the little guys

To many university leavers, the big graduate schemes seem like the holy grail – and missing out is a cause for despair. But are they really all that? Or are graduates just seduced by the structure that feels so familiar after years of full-time education?

Don't dismiss small- to medium-sized companies (SMEs, with less than 250 employees) – that's where the bulk of graduate vacancies lie. "Of the 60,000 graduate jobs in the UK, only 16,000 are with blue chip companies," says Hawes. "The remaining 44,000 are with SMEs, the public sector or charities." Thousands of SMEs are desperate to hire bright young graduates – but they may not advertise in the obvious places as it's expensive, so do some extra sleuthing to track them down.

7 Offer to help – but don't beg an employer for experience

Don't use your covering letter to tell a sob story about why you need a job to give you experience – however desperate you feel. And don't emphasise your potential – it sounds like you have nothing to offer (which isn't true). Instead, underline what you do have. Employers will hire you if they think you can help them – not because you need experience. And never offer to work for free. It looks as if you don't value your own contribution.

8 If it's really not working, it's time to stop doing it

The biggest mistake graduates make is repeating one job-hunting strategy again and again before wailing, "I've applied for 5,000 jobs and heard nothing back!" and the Daily Mail runs a story about it with a picture of them looking sad. It should never have come to that. After the first 50 applications, they should have stopped, reassessed and made a new plan.

Different industries require different approaches. Networking won't get you a public sector job – the procedure there is formal and structured. Few media people have ever filled out an application form – it's all about contacts and grabbing opportunities. Have the courage to ditch what isn't working – and try something new which might. What have you got to lose?

9 All the experience you have gained is good experience

Spent last summer litter-picking at Glastonbury and serving strawberries at Wimbledon? However lame you think your experience sounds, anything is better than nothing. "The key is to make it sound relevant for the job you're applying for," says Hawes. "Think back and see the job through the eyes of an employer. What challenges did you face and how did you overcome them? What skills did you develop? What training did you have? This is all great stuff for applications and interviews."

10 Nobody wants to hire a robot

Yes, be professional when you're applying for jobs, but be yourself. Stiff, robotic graduates using business buzzwords incorrectly is a big no-no for recruiters. The world of work can seem intimidating but "Generation Y" jobseekers – anyone born between 1980 and 1995 – have more natural abilities than they realise.

Yes, be professional when you're applying for jobs, but be yourself. Stiff, robotic graduates using business buzzwords incorrectly is a big no-no for recruiters. The world of work can seem intimidating but "Generation Y" jobseekers – anyone born between 1980 and 1995 – have more natural abilities than they realise.

Having grown up with the internet – including Wikis and blogs – they instinctively work collaboratively. "Sharing information, new discoveries and contacts is natural to Gen Y – and that's a big asset," says Justine James, director at organisational development consultancy talentsmoothie.

"Older workers hoard their knowledge and connections. Gen Y see no divide between social and professional networks, either – and a willingness to use a broad range of contacts is attractive to growing companies."

Friday, June 8, 2012

What To Do With A Degree In Fine Art

By Graham Snowdon

The Guardian,

The Guardian,

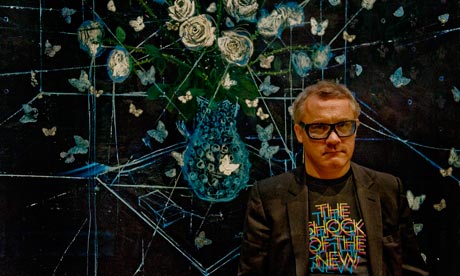

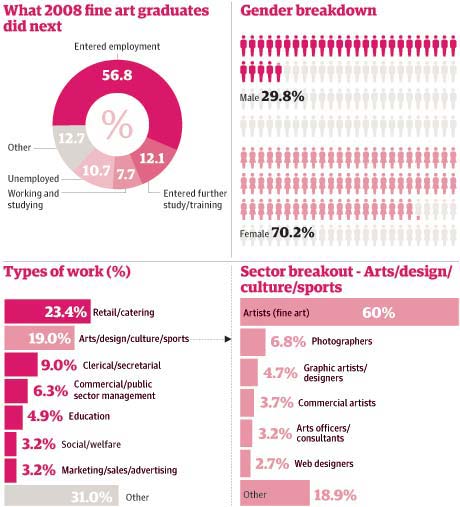

Fine art graduate Damien Hirst. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian

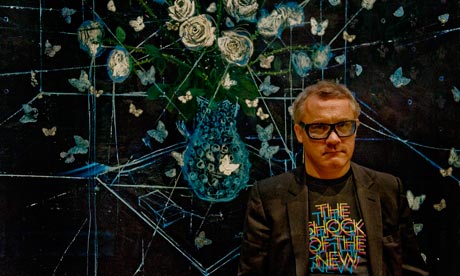

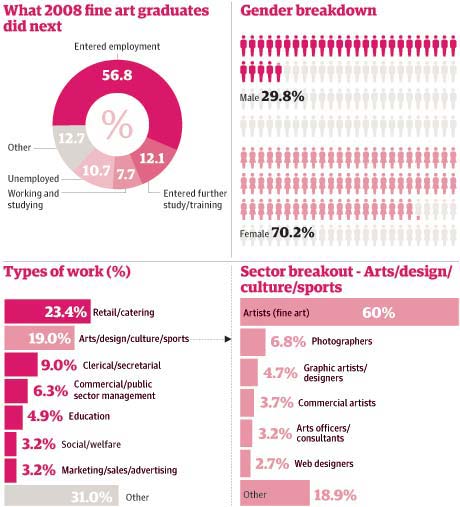

It's often said that one must suffer for one's art and, for aspiring artists, a spell of pennilessness after graduating has historically been de rigueur. This is as true today as ever, shown not only by the fact that 10.7% of 2008 fine art graduates were unemployed after leaving university (see graphic), but also by the high proportion listing catering or retail work as their primary occupation.

On the bright side, in between the waiting shifts you'll have plenty of time to polish your artistic skills and cultivate a brooding sense of existential angst. Just remember to take the long view; while arts funding will be scarce in the coming years, recessions have historically allowed creativity to flourish, as fine art graduates of the late 80s and early 90s, such as Damien Hirst (pictured) showed.

As our data also shows, fine art graduates splinter off into a broad range of career directions, from teaching to management to media and advertising.

Art is often a solitary pursuit so you should also have a good idea of how to motivate yourself and research ideas, materials and equipment.

The creative arts sector has more to offer though and roles in art galleries and museums, theatre, film and crafts would be suited to fine art graduates.

Holbrough points out that in business, the artistic flair of fine art graduates is also recognised in roles where the visual image is paramount, such as advertising and marketing, exhibition design, publishing and illustrating.

"Teaching, art therapy and working for community arts projects offer more socially and educationally focused careers, plus arts administration and management would give an alternative perspective to the arts," she says.

Data supplied by the Higher Education Careers Services Unit and Graduate Prospects

Data supplied by the Higher Education Careers Services Unit and Graduate Prospects

On the bright side, in between the waiting shifts you'll have plenty of time to polish your artistic skills and cultivate a brooding sense of existential angst. Just remember to take the long view; while arts funding will be scarce in the coming years, recessions have historically allowed creativity to flourish, as fine art graduates of the late 80s and early 90s, such as Damien Hirst (pictured) showed.

As our data also shows, fine art graduates splinter off into a broad range of career directions, from teaching to management to media and advertising.

What skills have you gained?

First and foremost you should have begun accumulating a hefty portfolio of work with which to showcase your technical and creative talents. The theoretical side of your degree should enable you to put your work into proper context, explaining your influences, the reasoning behind your choice of subjects and why you used certain materials.Art is often a solitary pursuit so you should also have a good idea of how to motivate yourself and research ideas, materials and equipment.

What jobs can you do?

"Fine art graduates often specialise in a particular form of art such as painting, drawing, installations, sculpture or printmaking but finding regular work or a permanent job as an artist is not easy and for some, self-employment, short-term residencies or commissions are the main career opportunities," says Margaret Holbrough, careers adviser at Graduate Prospects. It can take time to establish yourself as an artist while building up a credible portfolio.The creative arts sector has more to offer though and roles in art galleries and museums, theatre, film and crafts would be suited to fine art graduates.

Holbrough points out that in business, the artistic flair of fine art graduates is also recognised in roles where the visual image is paramount, such as advertising and marketing, exhibition design, publishing and illustrating.

"Teaching, art therapy and working for community arts projects offer more socially and educationally focused careers, plus arts administration and management would give an alternative perspective to the arts," she says.

Postgraduate study?

More than 12% of 2008 fine art graduates went on to further study, many taking master's courses to specialise in particular areas of art. Shorter courses specialising in certain related aptitudes, such as smithing, are also popular. A significant proportion go on to take a Postgraduate Certificate of Education, qualifying them to teach art in schools. Data supplied by the Higher Education Careers Services Unit and Graduate Prospects

Data supplied by the Higher Education Careers Services Unit and Graduate Prospects Thursday, June 7, 2012

10 Things Ive Learnt In The Two Years Since I Graduated From Art School

2. The Internet is the world’s most powerful tool. With great power, comes… you know the rest… or maybe you don’t, since you’re scrolling through facebook or tumblr. The way you share creations is almost as important as the creations themselves.

3. Advertising is worth the shame. My first illustration job out of college paid 20 dollars an image — a feeling not unlike getting mugged by a paraplegic sloth — yet every time those 20 dollars filled an empty wallet, my name and sites were sent off into the ether to hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people. Now some of those people pay me 100x-1000x that for illustrations. Why? Maybe because I make nice things, but more likely? Because with every underpaid image I made, I made someone, somewhere, remember my name.

4. Don’t “fuck the haters”, embrace the hivemind. The “haters” will come in many forms: sometimes with criticism based on personal preference, sometimes with nonsensical attacks that seem like youtube commenter vomit, and sometimes with actual advice disguised as “hate”, saying what

you’re doing wrong and what you could be doing better. Not everyone is a sage, not everyone is right, but they are worth listening to, if only to put a pin in to see if you hear something like that again. You will literally never be above improvement. There is no plateau, keep climbing, and pay attention to what’s around you, even the guy shouting through a megaphone while jackhammering directly underneath a potential avalanche.

5. Waiting for inspiration is like waiting at the DMV: It lasts forever and if you don’t know enough, you’ll probably still fail at the end. Nike your problems away by just doing it… “it” being something. You can wait and wait for good ideas, you can consume books, magazines, websites, and music by the truckload, desperate for something to trigger some sort of eureka moment, but if you just write your shitty lyric down, lay your shitty brush stroke down, or take your shitty photo, you’re on the right to track to actually making something good. I have made many terrible things, some of which remain terrible but served as stepping stones to better things, some I transformed into rather nice things, and I learned more about myself, the world, my work, technique, appeal, and a million other tiny factors from simply doing something, even when it failed.

6. Work to play. Be an idiot when you’re young, like… college-young. I was quite an idiot in college but I could have been even more of one and probably have been just fine. However, when you leave… leave the party there. If you give up a lot when you leave your childhood behind, and put your all into boring grown-up things like “work”, “money”, and “responsibility”, it genuinely doesn’t take much time to get the freedom you had in college back. The only difference is that instead of keeping the party going to distract yourself from a job you hate and rent you can barely pay, you can kick back and enjoy the party when you choose to on your own terms, if you even care about doing so at all. In other words: Stop it with this YOLO nonsense, why you are taking the words of a filthy-rich, diamond-selling recording artist who was on a Canadian TV show’s acronym of wisdom to mean: “be an idiot always and forever because fuck it, I’m young”, is beyond me. He worked hard to be able to wear $6000 socks, he didn’t “You Only Live Once” his way to them.

7. There are a lot of people more talented than you, that’s something you should know, but never accept. I’m regularly embarrassed by the quality of my work when I look at the hordes of artists superior to me, but you have time to spend, knowledge to gain, and skills to practice for the rest of your life. Your place amongst the world has no finality to it, you can always be more.

8. A friend who will stab you with a knife in the front is worth your weight in unicorn blood. Friends will back pat and backstab, occasionally becoming bloat and baggage, but if you should be so lucky as to find a person who cares about your success enough that they will outwardly knock you down a peg or ten with the truth so that you can better yourself, don’t toss them for the easier friend. Even lone-wolf-alpha-dog-max-pa

9. Karma is a pretty damn good business model. I have hunted for clients before. I have barked up their trees, aggressive and hungry for work, failing to get it every time. I have also done a lot of personal work, just for fun, but executed seriously. Many of these would be labelled as “fan art” — depictions of pop-culture icons with my own odd twist that I put out into the world — some of which I pour dozens of hours into. Traditionally, when I finish work with a client, I ask: “So, how did you find me?” almost every time the answer is: work of mine they saw on the web that I did for shits and giggles. I put good in, and in time (thanks to item #2), I get good out. There is no science or stability to this beyond the notion that if you work hard enough and if you can make your work seen, you will be rewarded. These are the naive musings of a 23 year-old, remember?

10. “Art” is a shitty word that people will tack on to anything these days. Just focus on creating, whatever that may be, however that may be, do it well, and do it because you love it.

By Sam Spartt

Monday, May 14, 2012

Anish Kapoor

Anish Kapoor: The Origin of the World (2004)

The whole exhibition space is the work, with a gigantic void in a slope that rises up from the floor. The void appears endless, broadening into its depth, and seems to encroach upon the observer, controverting conventional concepts of space.

Anish Kapoor, Indian-born British sculptor known for his use of abstract, biomorphic forms and his penchant for rich colours and polished surfaces. He is also the first living artist to have been given a solo show at the Royal Academy of Art in London.

Kapoor was born in India to parents of Punjabi and Iraqi-Jewish heritage. He moved to London to study at the Hornsey College of Art (1973–77) and the Chelsea School of Art (1977–78). A return visit to India in 1979 sparked new perspectives on the land of his birth. These were reflected through his use of saturated pigments and striking architectural forms in bodies of work such as 1000 Names. Created between 1979 and 1980, this series consisted of arrangements of abstract geometric forms coated with loose powdered pigments that spilled beyond the object itself and onto the floor or wall.

During the 1980s and ’90s Kapoor was increasingly recognized for his biomorphic sculptures and installations, made with materials as varied as stone, aluminum, and resin, that appeared to challenge gravity, depth, and perception. In 1990 he represented Great Britain at the Venice Biennale with his installationVoid Field, a grid of rough sandstone blocks, each with a mysterious black hole penetrating its top surface. The following year he was honoured with the Turner Prize, a prestigious award for contemporary art. Kapoor continued to explore the idea of the void during the remainder of the decade, creating series of works that incorporated constructions that receded into walls, disappeared into floors, or dramatically changed depth with a simple change in perspective.

![Artist Anish Kapoor’s 110-ton sculpture Cloud Gate.

[Credit: © Index Open] Artist Anish Kapoor’s 110-ton sculpture Cloud Gate.

[Credit: © Index Open]](http://media-3.web.britannica.com/eb-media/61/100661-003-880502CA.gif) In the early 21st century Kapoor’s interest in addressing site and architecture led him to create projects that were increasingly ambitious in scale and construction. For his 2002 installation Marsyasat the Tate Modern gallery in London, Kapoor created a trumpetlike form by erecting three massive steel rings joined by a 550-foot (155-metre) span of fleshy red plastic membrane that stretched the length of the museum’s Turbine Hall. In 2004 Kapoor unveiled Cloud Gate in Chicago’s Millennium Park; the 110-ton elliptical archway of highly polished stainless steel —nicknamed “The Bean”—was his first permanent site-specific installation in the USA. For just over a month in 2006, Kapoor’s Sky Mirror, a concave stainless-steel mirror 35 feet (11 metres) in diameter, was installed in New York. Both Cloud Gate and Sky Mirror reflected and transformed their surroundingd and demonstrated Kapoor's ongoing investigation of material, form and space.

In the early 21st century Kapoor’s interest in addressing site and architecture led him to create projects that were increasingly ambitious in scale and construction. For his 2002 installation Marsyasat the Tate Modern gallery in London, Kapoor created a trumpetlike form by erecting three massive steel rings joined by a 550-foot (155-metre) span of fleshy red plastic membrane that stretched the length of the museum’s Turbine Hall. In 2004 Kapoor unveiled Cloud Gate in Chicago’s Millennium Park; the 110-ton elliptical archway of highly polished stainless steel —nicknamed “The Bean”—was his first permanent site-specific installation in the USA. For just over a month in 2006, Kapoor’s Sky Mirror, a concave stainless-steel mirror 35 feet (11 metres) in diameter, was installed in New York. Both Cloud Gate and Sky Mirror reflected and transformed their surroundingd and demonstrated Kapoor's ongoing investigation of material, form and space.Thursday, May 10, 2012

Victor Hugo: Tachism

Saturday, May 5, 2012

Christian Boltanski

CHRISTIAN BOLTANSKI

"La vie possible"

15 May – 06 September 2009

Christian Boltanski, born in France in 1944, is one of the most internationally acclaimed artists of our time. In 2006 he was awarded the Praemium Imperiale, the Nobel Prize for the Arts presented by the Japanese Imperial Family.

Under the heading "La vie possible", the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein is devoting the largest retrospective exhibition in the German-speaking area since 1991 to Christian Boltanski. It surveys the development of this artist’s oeuvre since the mid-1980s, beginning with a series of the most famous Monuments. The main focus of the exhibition, however, is on his works of the past fifteen years. In a representative cross-section through all the groups of this time-period, plus works produced specially for the exhibition, La vie possible aims to facilitate an experience of the vitality with which the artist explores the possibilities of life itself, "real" life, but also collective life: la vie possible – not only is life basically possible, it is also full of potential for further development.

In the past three decades Boltanski has become an exponent of the "culture of memory" with his spacious installations and the very atmospheric settings of his works. The artist’s images make a complex impact. His intention is not to erect permanent monuments, but to activate memory, i.e., to promote a culture of memory that constantly underscores the living in the face of what has been lost. The Les archives du coeur project in which the artist is in the process of installing an archive of humanity’s heartbeats on the island of Ejima in southern Japan, is also to be seen in this context.

The exhibition illustrates the magnitude with which Boltanski’s work has developed and changed over this period. Works on loan from different museums, but above all from the artist himself, demonstrate how strictly Boltanski has thematically re-oriented his work over about two decades. Very new and as yet unseen works are also on show in the exhibition, which is being produced by the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein and curated by Friedemann Malsch.

Publication

To accompany the exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, the interview book La vie possible de Christian Boltanski, which appeared in France in 2008, will be published in a German translation (by Barbara Catoir) by Buchhandlung Walther König, Cologne.

"La vie possible"

15 May – 06 September 2009

Christian Boltanski, born in France in 1944, is one of the most internationally acclaimed artists of our time. In 2006 he was awarded the Praemium Imperiale, the Nobel Prize for the Arts presented by the Japanese Imperial Family.

Under the heading "La vie possible", the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein is devoting the largest retrospective exhibition in the German-speaking area since 1991 to Christian Boltanski. It surveys the development of this artist’s oeuvre since the mid-1980s, beginning with a series of the most famous Monuments. The main focus of the exhibition, however, is on his works of the past fifteen years. In a representative cross-section through all the groups of this time-period, plus works produced specially for the exhibition, La vie possible aims to facilitate an experience of the vitality with which the artist explores the possibilities of life itself, "real" life, but also collective life: la vie possible – not only is life basically possible, it is also full of potential for further development.

In the past three decades Boltanski has become an exponent of the "culture of memory" with his spacious installations and the very atmospheric settings of his works. The artist’s images make a complex impact. His intention is not to erect permanent monuments, but to activate memory, i.e., to promote a culture of memory that constantly underscores the living in the face of what has been lost. The Les archives du coeur project in which the artist is in the process of installing an archive of humanity’s heartbeats on the island of Ejima in southern Japan, is also to be seen in this context.

The exhibition illustrates the magnitude with which Boltanski’s work has developed and changed over this period. Works on loan from different museums, but above all from the artist himself, demonstrate how strictly Boltanski has thematically re-oriented his work over about two decades. Very new and as yet unseen works are also on show in the exhibition, which is being produced by the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein and curated by Friedemann Malsch.

Publication

To accompany the exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, the interview book La vie possible de Christian Boltanski, which appeared in France in 2008, will be published in a German translation (by Barbara Catoir) by Buchhandlung Walther König, Cologne.

Thursday, May 3, 2012

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Kasey Collective Exhibition

Thursday, 5th of April, 6pm – The Front Lounge

Kasey Collective is an exhibition which i am involved in where funds rasied are in aid of The Kasey Kelly Trust Fund. Kasey Kelly is a one year old girl who has been diagnosed with AT/RT Cancer (Atypical Teratoid Rhabdoid Tumor). She is currently in Crumlin Hospital, but the life saving treatment she needs to survive is not available to her here in Ireland. As a result her family need to raise €500,000 to send her to Boston to get the care she requires. Kasey Collective brings together the work of dozens of artists from many different backgrounds, who between them have many different styles, but who do have one thing in common – they all wanted to help raise the vital funds for Kasey’s treatment. The exhibition is sure to have something for everyone – from the street art style of Maser’s work, Adrian and Shane’s skillful stencil-work, Will St. Leger’s always comical commentary on Irish society and many more.

The audience is offered two different ways of purchasing works. The first way is a guaranteed-to-win raffle. Raffle tickets will be sold on the night, which guarantees the purchaser a piece of work, they just don’t know which work. At the end of the night numbers will be pulled and purchasers will be informed which piece they have won. All works not in this category will be priced, but will also have an option to ‘make an offer’.

This is an event not to be missed, come have a great night, check out the artwork and help a great cause at the same time.

Other participating artists include Solus, Fink, Emma Blake, Jess Szepsy, Donna Kelly, Claire McCluskey, Orla McNally, Kate Stitt, Maeve O’Flaherty, Aine O’Flaherty, Mark O’Toole, Emma Ray, Mason McMillen, Jennifer Quigley, Cats Byrne, Hannah McMillen, Thomas Moran, Sarah Murphy, Sarah Fitzpatrick, Derbhla Leddy, Doug Barratt, Emma Brown, Nicola Carragher, Aisling Ní Chlaonadh, Alan O Reilly, Paul Bailey, Debbie Hopkins, Adrian Langtry, Keith Kavanagh, Dona Stankune, Steph Gallagher, Paul McGrane, Marc Guinan, Marie Cowley, Maria Quigley, Aisling McKenna, Rosslyn Cowley, Linda Byrne, Bridie Farrell, Sarah Carney, Melinda Kugyelka, Chris Dicker, Martin Baker, Lucie Pacovska, Aurélie Montfrond, Deirdre Spain, Caroline Sweeney, Paul Aherne and Anto Ross (of Spilled Ink Tattoo Studio).

The exhibition will be open for the public to preview the work from Sunday the 1st of April.

If you would like to know more about The Kasey Kelly Trust Fund, or how you can help Kasey get her treatment go to her website www.kare4kasey.com or Facebook page www.facebook.com/kaseykellytrustfund

Special thanks to Martin Baker, for generously offering us the first week of his exhibition time in The Front Lounge. Martin’s photography exhibition will open on Saturday 7th of April in The Front Lounge, and will be showing for three weeks. Make sure to pop in and check out his work. Martin’s website is www.MartinBakerPhotography.com

Facebook event page

Facebook page

Twitter page

The audience is offered two different ways of purchasing works. The first way is a guaranteed-to-win raffle. Raffle tickets will be sold on the night, which guarantees the purchaser a piece of work, they just don’t know which work. At the end of the night numbers will be pulled and purchasers will be informed which piece they have won. All works not in this category will be priced, but will also have an option to ‘make an offer’.

This is an event not to be missed, come have a great night, check out the artwork and help a great cause at the same time.

Other participating artists include Solus, Fink, Emma Blake, Jess Szepsy, Donna Kelly, Claire McCluskey, Orla McNally, Kate Stitt, Maeve O’Flaherty, Aine O’Flaherty, Mark O’Toole, Emma Ray, Mason McMillen, Jennifer Quigley, Cats Byrne, Hannah McMillen, Thomas Moran, Sarah Murphy, Sarah Fitzpatrick, Derbhla Leddy, Doug Barratt, Emma Brown, Nicola Carragher, Aisling Ní Chlaonadh, Alan O Reilly, Paul Bailey, Debbie Hopkins, Adrian Langtry, Keith Kavanagh, Dona Stankune, Steph Gallagher, Paul McGrane, Marc Guinan, Marie Cowley, Maria Quigley, Aisling McKenna, Rosslyn Cowley, Linda Byrne, Bridie Farrell, Sarah Carney, Melinda Kugyelka, Chris Dicker, Martin Baker, Lucie Pacovska, Aurélie Montfrond, Deirdre Spain, Caroline Sweeney, Paul Aherne and Anto Ross (of Spilled Ink Tattoo Studio).

The exhibition will be open for the public to preview the work from Sunday the 1st of April.

If you would like to know more about The Kasey Kelly Trust Fund, or how you can help Kasey get her treatment go to her website www.kare4kasey.com or Facebook page www.facebook.com/kaseykellytrustfund

Special thanks to Martin Baker, for generously offering us the first week of his exhibition time in The Front Lounge. Martin’s photography exhibition will open on Saturday 7th of April in The Front Lounge, and will be showing for three weeks. Make sure to pop in and check out his work. Martin’s website is www.MartinBakerPhotography.com

Facebook event page

Facebook page

Twitter page

Sunday, March 25, 2012

"Paroda Pedagogy" Exhibition

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)